In 1904, Gustav Giemsa introduced a mixture of methylene blue and eosin stains. 14, 15 In this situation, a majority of the population is chronically parasitemic malaria may be concomitant but not the responsible agent of the febrile illness. Only in children in high-transmission areas can clinical diagnosis determine the treatment decision. 7, 8 Studies of fever cases in populations with different malaria-attributable proportions from Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Mali, Chad, Tanzania, and Kenya have shown a wide range of percentages (40–80%) of malaria over-diagnosis and its associated potential for economic loss. No single clinical algorithm is a universal predictor. 5, 6Īccuracy of a clinical diagnosis varies with the level of endemicity, malaria season, and age group. Although highly debatable, this practice was understandable in the past when inexpensive and well-tolerated anti-malarials were still effective. However, the overlapping of malaria symptoms with other tropical diseases impairs its specificity and therefore encourages the indiscriminate use of anti-malarials for managing febrile conditions in endemic areas. 4 This review focuses on microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), the two malaria diagnostics that are likely to have the largest impact on malaria control today.Ĭlinical diagnosis is the least expensive, most commonly used method and is the basis for self-treatment. Confirmatory diagnosis before treatment initiation recently regained attention, partly influenced by the spread of drug resistance and thus the requirement of more expensive drugs unaffordable to resource-poor countries. Accurate diagnosis is the only way of effecting rational therapy. Rational therapy of malaria is essential to avoid non-target effects, to delay the advent of resistance, and to save cost on alternative drugs.

Despite an obvious need for improvement, malaria diagnosis is the most neglected area of malaria research, accounting for less than 0.25% ($700,000) of the U.S.$323 million investment in research and development in 2004. Scientific quantification or interpretation of the effects of malaria misdiagnosis on the treatment decision, epidemiologic records, or clinical studies has not been adequately investigated. 1, 2 Had accurate malaria diagnosis been achieved together with an improved public health data reporting system and healthcare access, such a conjecture would be lessened.Ĭlinical diagnosis is imprecise but remains the basis of therapeutic care for the majority of febrile patients in malaria endemic areas, where laboratory support is often out of reach. Any attempt to estimate the number of malaria cases globally is likely to become subject to argument. The wide range of 200 million in the frequently quoted “300–500 million cases per year” in itself reflects the lack of precision of current malaria statistics. An investment in anti-malarial drug development or malaria vaccine development should be accompanied by a parallel commitment to improve diagnostic tools and their availability to people living in malarious areas.

#RAPID DIAGNOSTIC TEST FOR MALARIA PLUS#

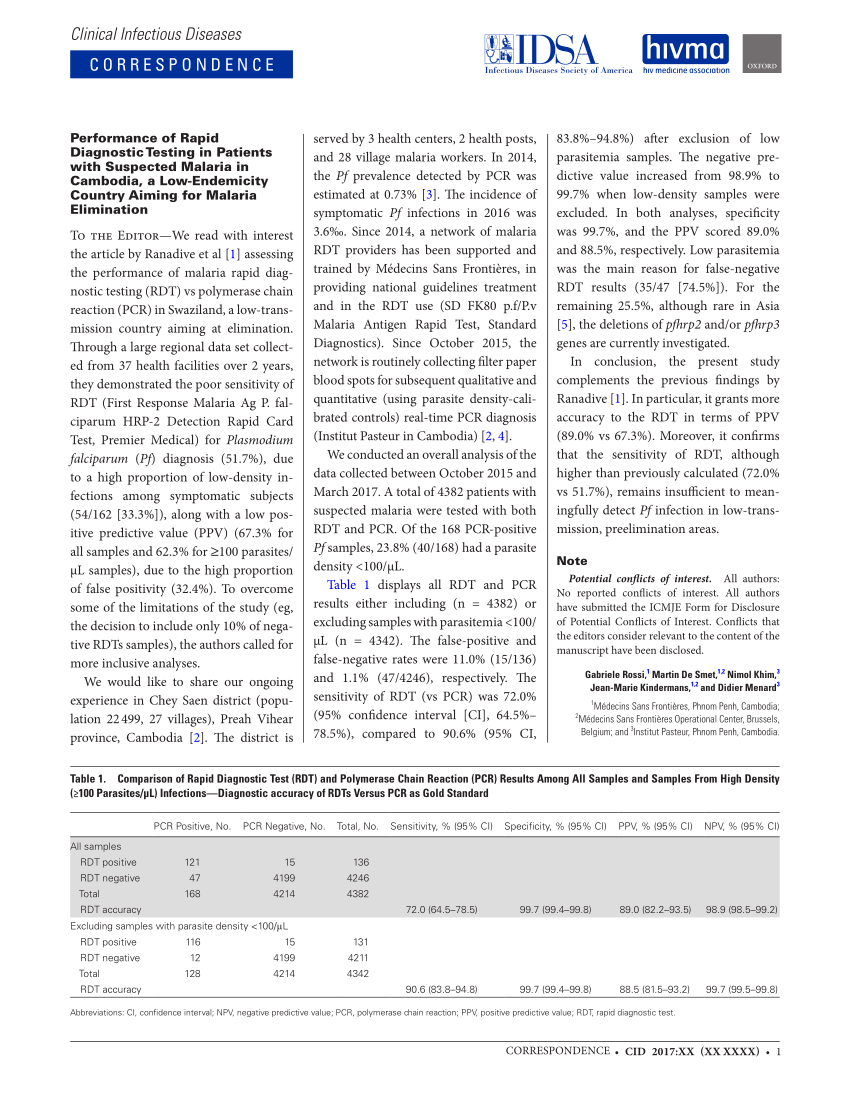

Reduction of malaria morbidity and drug resistance intensity plus the associated economic loss of these two factors require urgent scaling up of the quality of parasite-based diagnostic methods. This review addresses the quality issues with current malaria diagnostics and presents data from recent rapid diagnostic test trials. These two methods, each with characteristic strengths and limitations, together represent the best hope for accurate diagnosis as a key component of successful malaria control. Giemsa microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) represent the two diagnostics most likely to have the largest impact on malaria control today.

%20for%20malaria%20result%20in%20Rizal%2C%20Palawan%2C%20Philippines%3B%20Credit%20Joshua%20Paul.jpg)

The absolute necessity for rational therapy in the face of rampant drug resistance places increasing importance on the accuracy of malaria diagnosis.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)